Cousin to the Crown: From Colditz to the Palace Just in Time for VE Day

As she greeted VE Day veterans to her tea party at Buckingham Palace on Monday, Queen Camilla inevitably spared a moment to remember one valiant warrior who couldn’t be there – Her dad, the daring ex-cavalry officer Major Bruce Shand .

Shand, a career soldier and later wine merchant, who died in 2006, flew home from his two-and-a-half-year incarceration in a German prisoner of war camp just in time to celebrate VE Day with the crowds outside Buckingham Palace in May 1945.

Within the palace walls were two more recently released prisoners of war: King Charles’s great-uncle, George Lascelles (later the Earl of Harewood), and Charles’s first cousin once removed, John Elphinstone. Both had returned to Britain the night before.

Inmates of the notorious Colditz Castle, their well-being had been a cause of special anxiety for their uncle and aunt, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, due to their proximity to the throne. Shand, still years away from joining the royal circle, was perhaps the most distinguished soldier of the three, though the hardships they endured were shared by all.

Following his time at Rugby (where he remarked "a school I thoroughly detested"), Shand received his commission into the 12th Lancers, an illustrious cavalry unit formerly led by the legendary Duke of Wellington. By the age of 23, he had been awarded his initial Military Cross for actions during the Dunkirk evacuation. He earned another such commendation in January 1942 after displaying remarkable courage amidst attacks from the German Afrika Korps in the Western Desert region of North Africa.

In November 1942, during the Second Battle of El Alamein, Shand found himself under attack once more. His armoured vehicle was wrecked due to hostile gunshots, leaving him severely injured and taken prisoner. Following his capture, Shand experienced an extensive transit; initially sent to Greece before being moved further westward towards Spangenberg close to Frankfurt, joining approximately 300 other prisoners there. prisoner-of-war officers at the local 13th-century castle .

Shand had suffered debilitating injuries, nearly losing an eye and a leg, but his memories of the Spangenberg years remained upbeat and wry. Dunkirk, he recalled, was “unpleasant” while Spangenberg was “neither Shepherd’s nor Claridge’s”.

But in the early days of his imprisonment, Shand was haunted by waves of remorse over the loss of the two crew members in his vehicle. “They had considerable trust in me, a trust that had been betrayed, even if their deaths were blessedly instant,” he wrote. In hindsight, it’s clear Shand made no tactical error – he had simply been ambushed by the Germans.

At Spangenberg, he quickly learnt to rely on his wits. He delivered lectures to fellow prisoners on the progress of the war, but kept a decoy subject at the ready in case a guard entered unexpectedly. His chosen cover? “The flora and fauna of Lower Egypt and the seasonal fall and rise of the Nile.”

He was named as the security officer with the duty of managing whichever covert radio set could be assembled, at least up until its expected exposure by the sentries. His responsibilities included recording transmissions from beyond the prison walls and discreetly sharing this intel with his co-prisoners. Additionally, he took on the position of "laundry officer" — a title ostensibly related to laundry duties but practically centered around offering bribes to both guards and local launderesses for valuable bits of information gleaned through their work.

The extended periods of captivity were marked by chilliness, hunger, confinement, and gloom. Shand sought comfort in the prison library, devouring volumes on history, biographies, and personal accounts. During the warmer seasons, he was allowed to engage in gardening and woodcutting; however, when the colder winter nights fell and darkness prevailed, inmates passed their time through plays and educational talks.

Not all of these discussions proved enlightening," he remarked dryly in his memoirs. "Be it the Albigensian heresy, the confidential classifications within Bordeaux’s wine regions, the art of perfume making, the cultivation of racing pigeons, the study of heraldry, or even the Pentateuch — there was invariably an individual with expertise in these arcane subjects.

I think there might have been a pair or two of bagpipes, but their usage was strongly frowned upon.

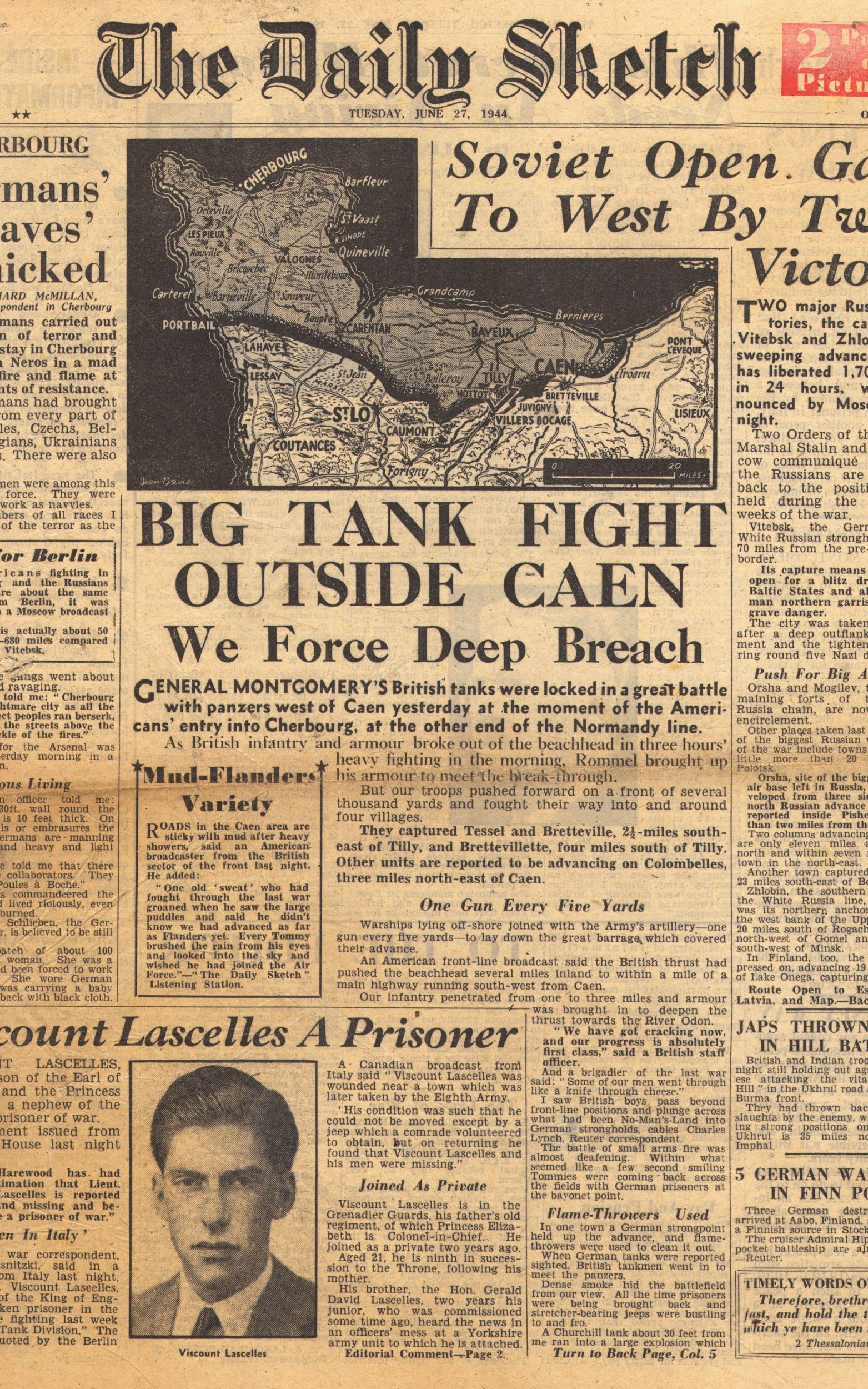

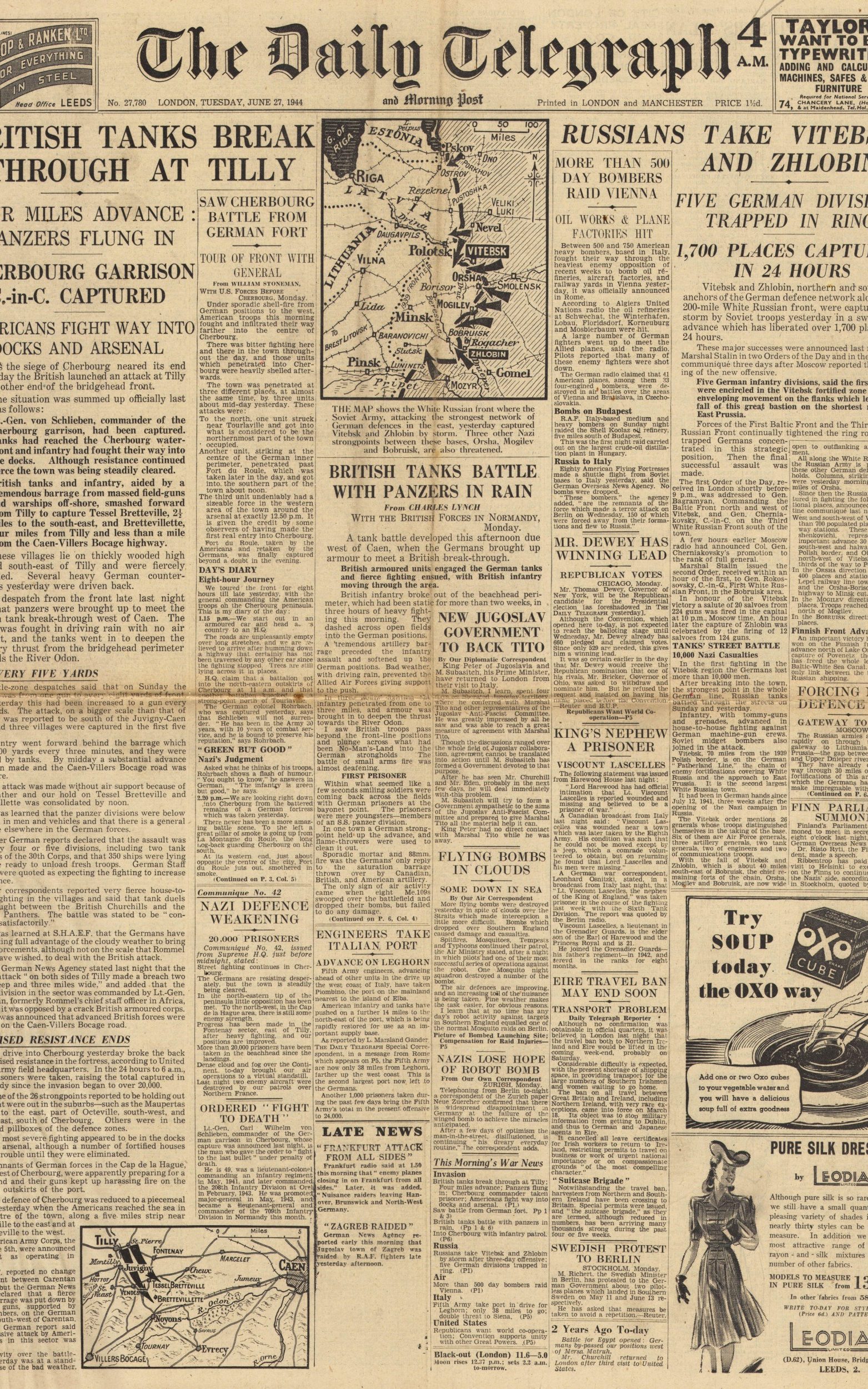

A passing acquaintance at Spangenberg was King George VI’s nephew, George Lascelles, son of his sister Mary, Princess Royal. A 21-year-old lieutenant in the Grenadier Guards, Lascelles had been captured after being wounded during the Italian campaign in June 1944.

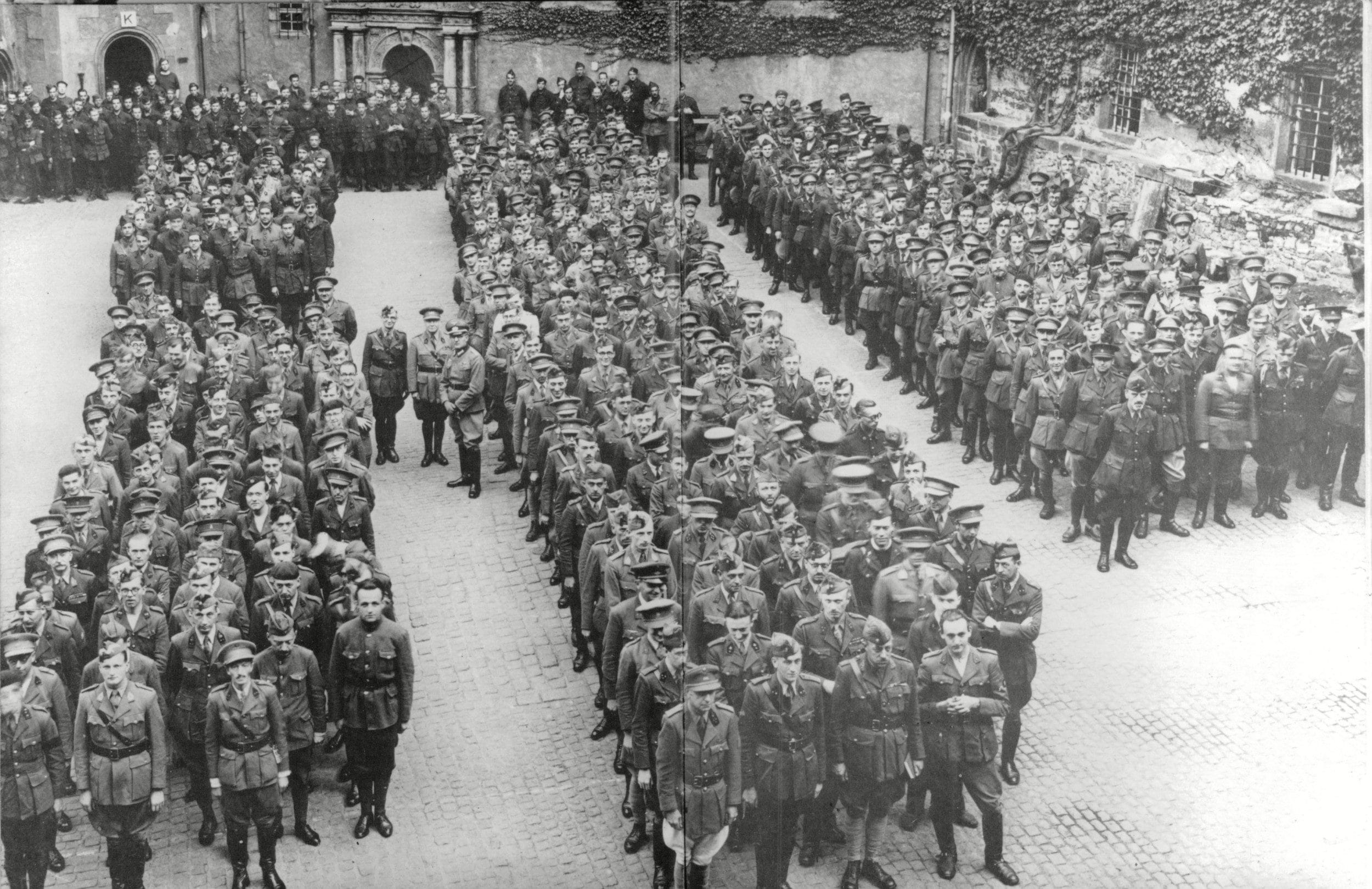

Soon Lascelles was moved on to Colditz Castle, 200 miles deeper into eastern Germany. “Everyone there either had a record of escape or some other punishable offence,” he recalled years later. “[My offence] was to have prominent relations.”

He became one of the Prominente — the term used by the Germans during the Second World War to refer to a special category of prisoners who were either actually or allegedly linked to influential figures. Elphinstone fell into this category as well.

In comparison to Spangenberg, the conditions at Colditz were significantly tougher and crueler—prisoners subsisted on meager portions providing just 1,100 calories daily: "Climbing stairs required either frequent stops or resulted in blackouts," as he remembered.

During much of his time over the wintertime, Lascelles passed most days with clothes on whilst lying in bed. As the conflict continued without end, numerous longtime captives - such as those taken prisoner at Dunkirk - started experiencing mental collapses; they could not bear how prolonged this waiting period became. Meanwhile, some individuals with stronger spirits chose to immerse themselves in writing activities. However, Lascelles—who went on to be an influential person within British opera—opted instead to learn playing the clarinet.

Poker lessons, music appreciation clubs, philosophy courses, history talks — we attempted various activities, whether intellectually stimulating or not, until ultimately, the harsh conditions overpowered us," penned Lascelles in his memoirs. "I came to understand that Colditz was like Redbrick compared to Spangenberg’s Oxbridge — possibly coarser maybe, definitely more vigorous, with an ambiance much less elevated.

One officer who kept very much to himself at Colditz was Elphinstone. Educated at Eton, he was among kindred spirits but somehow remained austere and apart. “He seemed to operate in a kind of deep freeze,” recalled Giles Romilly, a nephew of Clementine Churchill and another of the Prominente.

The Elphinstone family had been Scottish lairds since the 13th century and lived in considerable splendour. John, a lifelong bachelor, was a Black Watch officer among those forced to surrender at the Battle of Abbeville in 1940. He would spend nearly five years as a German prisoner, and his remoteness – along with his insistence on correctness in all things – was likely a defence mechanism. Yet, according to fellow PoW Martin Gilliatt (later Sir Martin, private secretary to the Queen Mother), he was “the kindest, most undemanding and understanding friend one could possibly have”.

Not everyone agreed. The senior officer among the Prominente, Elphinstone deplored sloppiness and shabbiness in dress among his fellow prisoners – and never hesitated to express his disapproval, harshly, despite the appalling conditions in which they were held.

The Queen felt a special closeness to her nephew, and he to her, after she visited his regiment and momentarily mistook him for her dead brother Fergus – another Black Watch officer – who had perished in the First World War. Though no blood relation to the Royal family, Elphinstone took his connections very seriously. When writing letters home, he referred to each member by the nicknames known only to them – his aunt, the Queen, was always given a boy’s name.

Despite this reclusive nature, he was to save the lives of his fellow Prominente as the Allies finally headed towards Colditz in late April 1945. “He was a personality that was to play a resolute, decisive and quite possibly providential part in the impending dangers,” declared Romilly.

As the Allies advanced, the Nazi high command issued the order to evacuate the camps. In both Spangenberg and Colditz, fear spread among the prisoners that they may be used as human shields, or merely taken out and shot. For the Prominente, there was the added threat that they might be handed over to the Gestapo, in whose hands they would most certainly perish.

Shand and his fellow inmates had to walk for two days toward the Wehra River, however, during the subsequent night, He and a handful of others drifted away from the column and took cover in the adjacent forest. "The downpour was intense, chilly, and an unsettling creepy sensation lingered as projectiles zipped above." Although this band was now technically liberated, roving clusters of individuals were still causing trouble. Hitler-Jugend — "quick-tempered teenagers" — posed an ongoing danger.

In due course, Shand’s group joined forces with advancing US Army units, who then transported Shand to Paris by air through Luxembourg.

His getaway was clever and fruitful, albeit fairly straightforward when contrasted with that of Elphinstone and the Prominente who had previously been held at Colditz. On one evening, these valuable prisoners were instructed to board a bus without being informed where they were headed, causing them considerable dread.

Their voyage led them initially to one detention facility, followed by another, until they reached a civilian internee camp in Laufen. There, they worried about losing their military standing, which could make them targets for removal. Typically reserved, Elphinstone spoke up forcefully, insisting they should be transferred to a military camp instead. He adopted an air of presumed control—“like he was in charge of both German and British forces”—and this approach succeeded; consequently, they were relocated to Tittmoning Castle in Bavaria.

The Prominente were resolute in their bid for freedom. At Tittmoning, they stumbled upon a hidden compartment inside the 6-foot-thick prison walls, which was likely used by earlier prisoners of war. On an eventful night, one of them sliced through the outer barbed-wire fence, giving the impression that they had fled into the surrounding landscape. However, they actually squeezed into this confined niche within the structure, planning to remain out of sight until either American or Russian forces reached them.

In its own manner, it wasn’t entirely lacking in luxuries," remarked Lascelles dryly. "There was a large tin bucket that functioned as a lavatory. It only accommodated two people at once, so we took turns sleeping in two-hour shifts, swapping spots whenever it was our time.

They endured for three days, attempting to read during the meagre daylight seeping through a gap in the wall, communicating solely with hushed voices. From this vantage point, it seems unfathomable how five men sustained their existence in an area not much larger than a substantial closet before ultimately being found.

Paradoxically, the camp commander felt relief upon seeing them return—he had faced a death sentence for permitting their earlier escape but was now granted clemency. Nonetheless, they found themselves herded back onto a bus and dispatched further without knowing if their special standing would lead to them being received as honored guests or met with execution at their final stop.

Actually, the Prominente had turned into pieces in a dangerous game, as Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who led the Gestapo, was keen to obtain these hostages. Additionally, they learned from General Berger, an SS officer, that he had been instructed by Hitler to execute them—though he claimed he did not intend to follow through with this order.

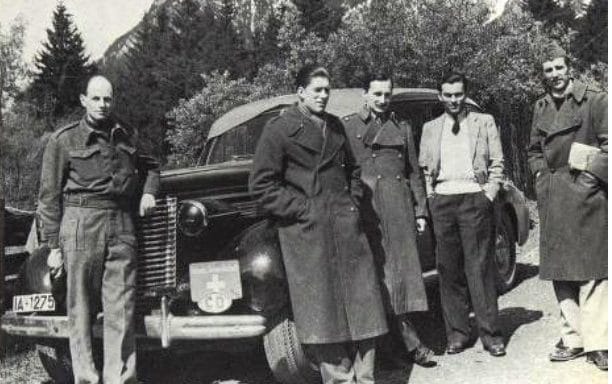

Berger organised for Elphinstone, Lascelles, and the others to be transferred to a transit camp located in Markt Pongau (now known as St Johann in Pongau). Here, they met with a Swiss go-between who assured them of secure passage into Allied custody. To potentially deter any future military intervention, an additional member was included in their party: a German physician prepared to surrender himself.

Finally transferred to a larger vehicle, the group slowly approached the Allied lines, fearful that a trigger-happy US soldier might open fire on the unfamiliar convoy. But they arrived safely in Salzburg, where, that night, Elphinstone received an unexpected call from the Queen. She insisted that he and Lascelles return immediately to Buckingham Palace, where a champagne-laden dinner awaited them.

On May 8th, 1945, Britain marked VE Day with great celebration. With former prisoners of war stepping aside, the royal family greeted the jubilant throngs from the balcony at Buckingham Palace.

Bruce Shand, still outside the royal circle, flew back from Paris, where he was warmly greeted by Rosalind Cubitt, the former debutante he had escorted to her pre-war coming-out dance – the last of peacetime. Once safely home, he proposed marriage.

Eight months later, the couple wed at St Paul’s Church, Knightsbridge. A year after that, Mjr Shand became the proud father of Camilla, the future Queen.

Recommended

I saw Bergen-Belsen through the eyes of a 94-year-old survivor returning for the first time

Read more

Play The Telegraph’s brilliant range of Puzzles - and feel brighter every day. Train your brain and boost your mood with PlusWord, the Mini Crossword, the fearsome Killer Sudoku and even the classic Cryptic Crossword.

No comments